If you’re just joining us, this is Entry #2 in our August, 2015 series celebrating the different interpretations of fiber art that we’ve loved seeing in past Internationals.

Fiber artists are particular about sourcing our materials. Mindful material use might enrich a work that focuses on a specific time or place, or help us achieve just the end result we want. We can grow our own dye plants, spin our own thread, weave just the right fabric to carry our point across. That’s part of the beauty of fiber as a medium.

But access to ready-made materials is an important part of our tradition too. The same eye for detail that leads one artist to hand-gather thousands of seeds for a project can lead another to source a pre-made fabric that infuses a piece with meaning and creates just as much impact on the viewer as something custom.

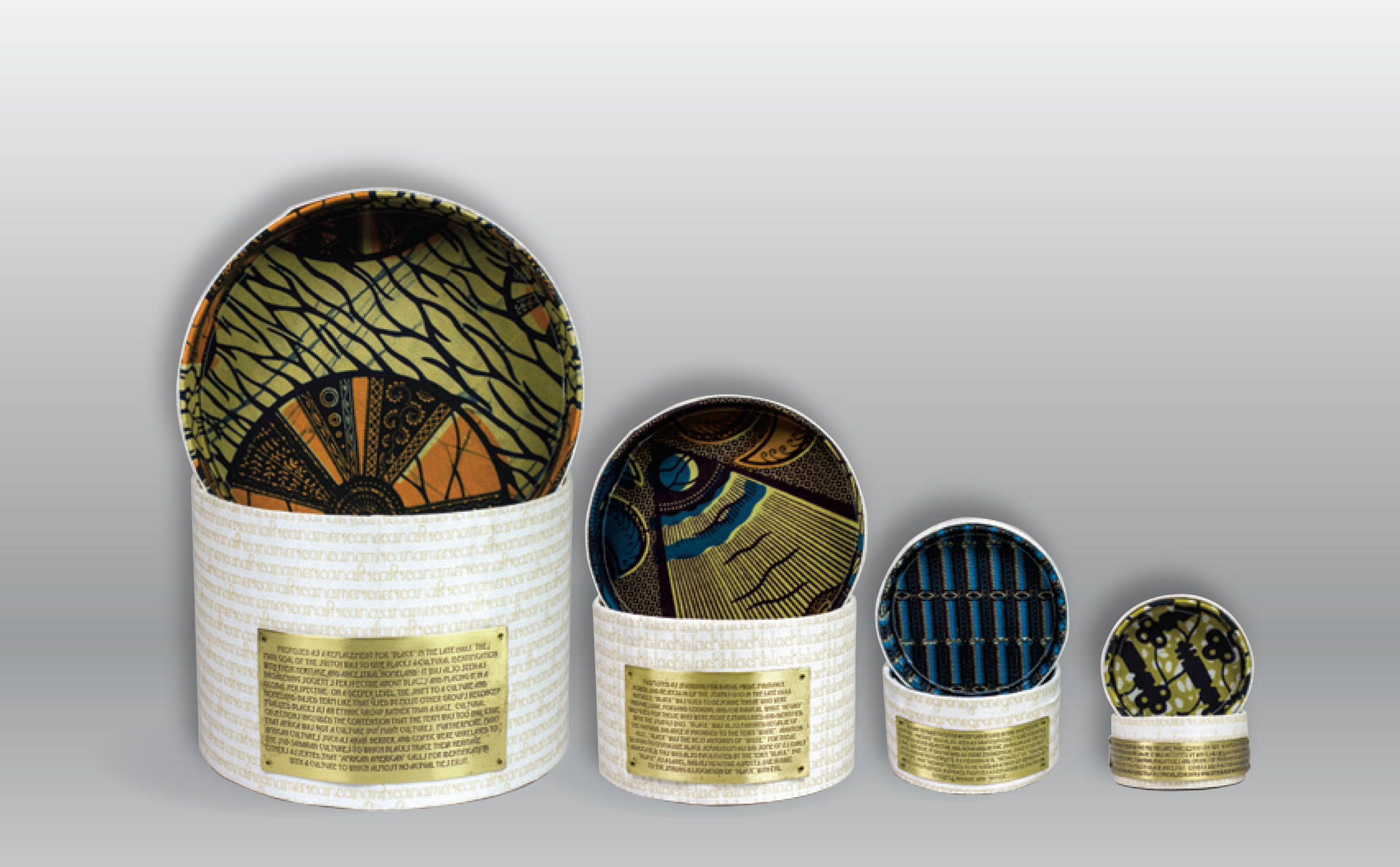

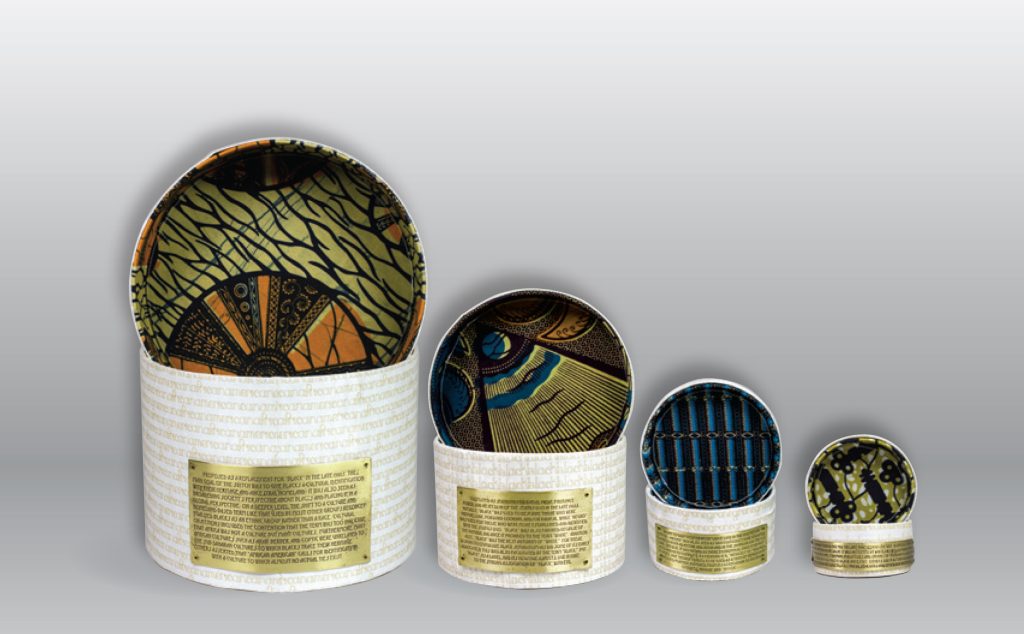

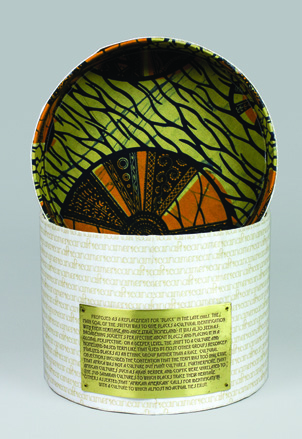

In her piece “Oh, You Know… The Colored Girl”, artist Joy Ude uses Nigerian wax cloth to line nesting boxes that tell a story about race relations, social injustice, and the fact that the names we choose to call each other reflect our society as a whole.

The outside of each box in the series is covered with a bland beige fabric printed with a different label that Black Americans have been called over time, repeated over and over. They are arranged in order of age, with the smallest box being the most outdated and the largest the most recent (bearing in mind the work was created in 2011). Starting with the smallest & oldest, the labels are: “colored,” “negro,” “black,” and “african american” (my lack of capitalization here reflects the artist’s choice not to capitalize these words on her work). The brass plaques on the front of each box detail Ms. Ude’s research into the historical context for each term.

Even though there’s still a lot of custom work that’s gone into this piece (the pale printed fabric on the outside of the boxes, the brass plates), it’s the bright Nigerian cloth on the inner lid that draws the eye and immediately gives the viewer a visual clue to the theme of the work.

Once you get close enough to read, the richness of the printed fabric defies the bland, pale labels. You’re left with the uneasy feeling that there’s still more story there to tell, and that the refined and repetitive outer covering is trying (and failing) to restrain the vibrancy within each box. It’s smart use of a ready-made material, and an effective way to create contrast between internal and external surfaces.

Read Joy’s artist’s statement about her piece below, and see more of her work here.

“In my artwork, I explore Black culture as a subset of American culture by addressing sociological issues involving education, employment, and race-relations. Though use of the term is not currently acceptable, I wondered if and when in America’s history the word “colored” was considered an acceptable label for Black Americans. I was also curious about additional racial labels from previous decades and generations that had fallen out of usage. I researched previous and current labels, their duration of use, and the events that fostered change in the way that Black Americans refer to themselves as a cultural group.”